Rapper-activist Keshad Adeniyi has visions of Black liberation from Watts all the way to Brooklyn

By Chioma Nwana

Following the release of his WhAt’s Real? EP, Los Angeles native and Brooklyn transplant Keshad Adeniyi wrote to SVGE Magazine about the project, the intersections of art and prison abolition, and his PhD dissertation.

A lot of artists are advised to start off with more commercially palatable music and later transition into their niche after they’ve built a fan base. What pushed you to release such a politically charged project so early in the game?

Nina Simone said, “You can't help it. An artist's duty, as far as I'm concerned, is to reflect the times,” and I agree with her. I also believe there’s great power in telling our stories—in sharing first-hand experiences that provide insight into how these moments in American history have impacted everyday people not only psychologically, but materially.

First, I come from something—a woman who gave birth to me while she was incarcerated and a Nigerian man who came to America in pursuit of something great. Both watched their children get taken from them and put into the foster care system as a consequence of their drug addiction.

I watched them get incarcerated. I watched my father get deported. I experienced the implications rendered by the lack of resources—rendered by both state violence and systemic racism—first-hand. Once I began to understand how the history of Black people in this country informed not only my upbringing, but the homies’ upbringing and my partner’s upbringing, my artistic approach began to reflect that truth.

This is what I’m informed by. This is what my life looks like daily. My music will always reflect where I’m at, what I’ve seen, and what I’m experiencing. It’s important that my intention is clear from the jump.

From what I understand, you have made advocacy for incarcerated folks your life’s mission. Talk to me about your personal connection to abolition.

This is such a critical element of my approach as an artist because I’m not the only one who has been impacted by the systems that the organizations we selected seek to tackle—the people in our community have been impacted as well. Some of the organizations we are working with right now are the LA-based Youth Justice Coalition, the LA-based Prison Education Project, and the Brooklyn-based exalt youth. All of these organizations attempt to undercut America’s carceral apparatus.

The Prison Education Project gave me my start in 2012. It was with them that I began to understand the implications of incarcerating Black people en masse. As I have grown, I have gotten deeper into the work, both academically and in practice. Both my political education and my personal relationship to the harm that these systems inflict are why I now identify as an abolitionist.

Since 2012, I have been contributing to this fight in a number of ways. My artistic ability is one way I contribute—I see my art as an entry point into many of the conversations that helped to inform how I now identify. The 30% of all merch and product sales that The Field has committed is a financial contribution. To make it simple, we see this effort as a way to invest into the organizations that are helping us to both manifest and envision an abolitionist world.

“Both my political education and my personal relationship to the harm that these systems inflict are why I now identify as an abolitionist.”

You’re currently in pursuit of a PhD at Howard University, but one can assume that your understanding of injustice and activism set in long before you entered any formal academic spaces. What did education outside of academia look like for you?

This is an interesting question. Most would assume that I have some type of fundamental relationship to race and all of its historical implications, but I don't. I know that’s odd based on my current academic journey, but none of these conversations were ever present at the crib, and beyond the personal ways these systems touched me, I don’t know that I really had a conversation about race until I was 21 or 22 years old.

The story of Trayvon Martin and the Prison Education Project played critical roles in my political education. Academia, just like my art, has been a tool to get people to engage with some of the critical questions that I believe must be answered before we can transform space. While I can give college credit for helping me and providing me access to engage in some of the first conversations I had about anti-policing, patriarchy, Black radical feminist tradition, and abolitionist discourse, my relationship to many of these threads became a personal one as I began to spend a lot more time inside of the prisons.

My experiences as a facilitator and educator inside of prisons have been critical to my viewpoint and intimacy with a specific type of information. For example, I was introduced to George Jackson’s Blood In My Eye through some of my early work inside of California facilities. These types of experiences inspired me to continue in my journey of knowing and understanding systems, institutions, and apparatuses alike.

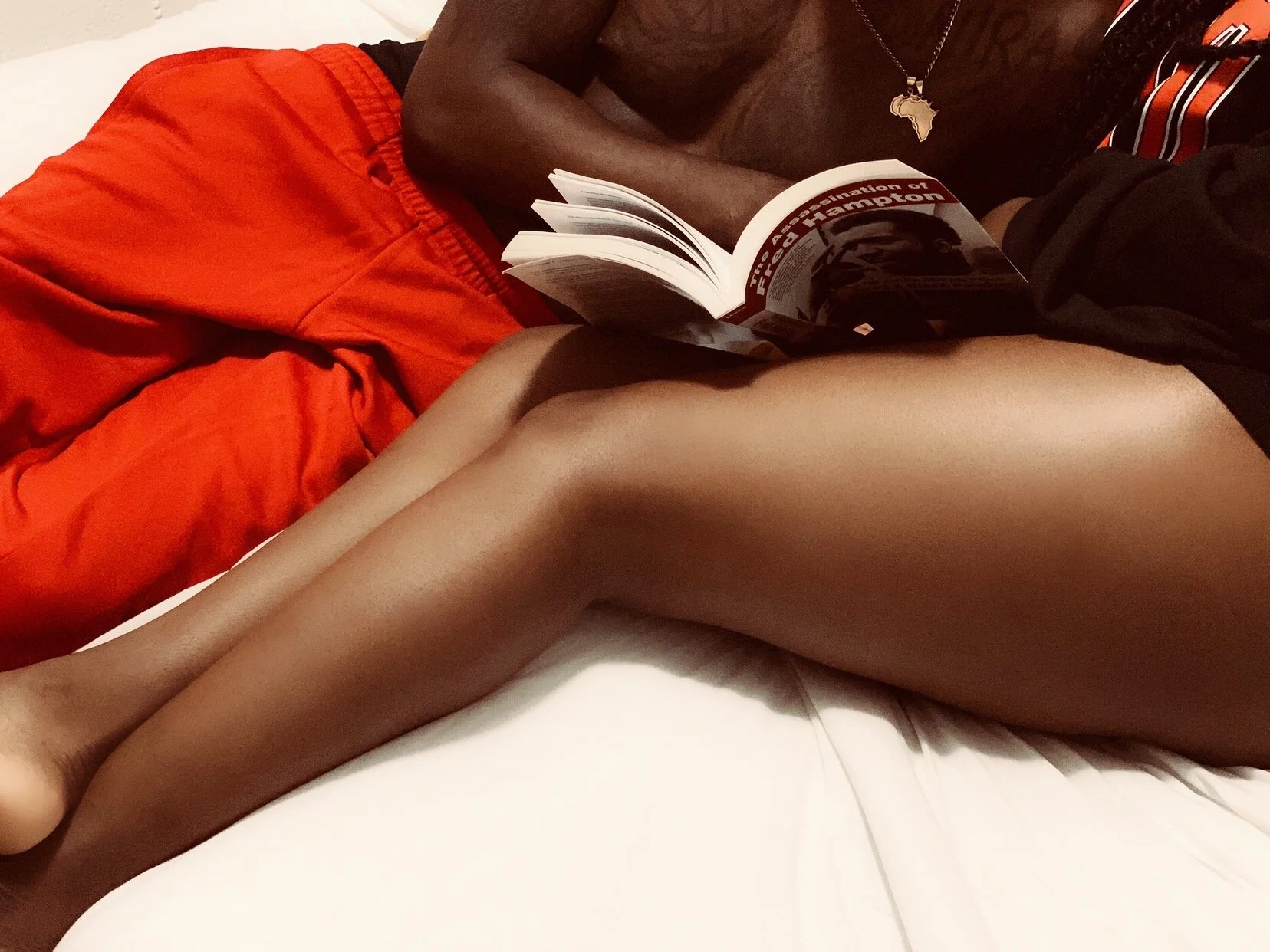

The EP booklet features a series of photos of you and your partner cohabiting. Was this creative direction intentional? If so, what message were you trying to get across?

Yes it was. My partner and I are essential to a very important part of the WhAt’s Real? concept. If the EP gives the listener insight into how a revolutionary, activist or artist informed by race can be conceived in a western world, then my partner and I provide an example of how love ties into that whole process.

I wanted Love to be the connecting theme because I think it’s sometimes missed in our generation’s stories about how they came to leadership or success. Oftentimes, the thread is that there is no space for love, right? It’s often asked, “Who can think about love when they are on the frontline or creating in prolific ways?” And I’m simply not informed by that. Love is first for me. How we get loved on and how we love on people—platonically and intimately—will have implications on how quickly and effectively we trek towards transformation.

The booklet also features Jeffery Haas’ The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther, a book that has radicalized and mobilized many people. If you could pinpoint three books that radicalized you, what would they be?

Given that my start in The Field was 2012, I’ll have to say that Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow was an initial step for me. Though it didn’t necessarily force me to see the world through a radical lens, it did, however, help me to understand how urgent it was to undercut neoliberal ideas concerning a post-racial country. It was Angela Davis’ Are Prisons Obsolete? and If They Come in the Morning and George Jackson’s Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson that radicalized my perspective of the world.

The first part of “Baldwin Ave” is a recording of you reading James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time to your newborn child. How have the teachings from this book manifested themselves in your own life?

I consider Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time an essential read, and I’d say it really forced me to understand my relationship, as a Black man, to the American state. For the longest, I struggled with identifying as an American, in part due to what it meant to be Black in this country historically but also because of the role it played in creating the wedge between Black Americans and Black Africans.

The Fire Next Time, along with an article written by Nikole Hannah-Jones in her 1619 project, helped me to understand what it means to take ownership in the American Project, and that’s why I started the EP the way I did.

For my child, I’d want her to come back here and hear me say, in Baldwin’s words, “This is your home, don’t be driven from it,” not only because she’d been birthed here but because she built it, and it has been her people who have historically modeled what this country says it is on paper.

“How we get loved on and how we love on people—platonically and intimately—will have implications on how quickly and effectively we trek towards transformation.”

You spend a lot of time working with youth in The Field, the name that you’ve given to prisons, jails, and classrooms filled with communities that have been harmed by carceral apparatuses. What did your journey to youth justice look like?

My journey towards youth justice runs concurrently with my journey as an activist. It all started in 2012, but I think my work in juvenile prisons in 2015 provided me insight into the few areas of the country where larger populations of people tend to agree—most of us tend to be a lot more forgiving of a specific action depending on the age a person was when they did the things many of us struggle to forgive.

Youth justice then is a very instrumental space. Space. It’s a space where we have an opportunity to help shape the country and how it understands retribution, crime, and punishment. Youth justice helps me to understand people and their relationship to punishment paradigms. I think when we get to a place where we are satisfied with how justice plays out alongside youth, it will provide us a framework that we can apply to all people who are traversing a number of institutions and systems that cause harm and do violence to everyday people.

“Youth justice helps me to understand people and their relationship to punishment paradigms.”

What comes next for your music, for your activism, and for your education?

For music, it’s really just me sitting back and figuring out when I want to say something else and what it will be. I have another project I created during the pandemic that I am hoping to drop this year, along with some singles, if it makes sense to do so.

But for activism, the world informs me accordingly. The struggle is an everyday one, and I am always strategizing around how I can infuse my everyday struggles with my art in general. I’m hoping the next time I pop out with new art, I would have thought about refreshing ways to continue using it as an entry point to either bring awareness or build community.

Lastly, I’m forever a student of something! But formally, I’m scheduled to complete my PhD from Howard University in June 2022. Finding the time to write this dissertation means I have to pause the art and that has never been an easy task for me. But I believe I’ll get it done.

What’s your dissertation on?

My dissertation is on the state’s usage of impressment during the Civil War as a way to control Black labor. Fundamentally, there are a number of things that are true to the carceral state today that were critical to the Black experience during the Civil War like labor exploitation, confinement, policing, surveillance, and compulsion. I’m probing how such methods existed on a continuum that has stretched into the contemporary moment.