Meet Polo Silk, the photo historian whose lens has changed the world’s perception of Black New Orleans

By Andre Uncut

Polo Silk, photographed by Andre Uncut.

“For a lot of years, we’ve been known as the murder capital. I want my photos to show that it’s not all that bad.”

Published photographer, cultural archivist, and human New Orleans hip-hop encyclopedia Sthaddeus “Polo Silk” Terrell has been photographing his city since the late ‘80s. With his ride-or-die camera Chelsey in tow, Polo Silk has had the same mission for over three decades: capturing what New Orleans means to Black people and—maybe more importantly—what Black people mean to New Orleans.

In April, Polo sat down and caught up with fellow photo historian and friend, Andre Uncut, to walk through the abridged version of his biography and the Black history of New Orleans for SVGE Magazine.

Go ahead and introduce yourself.

I am Sthaddeus Terrell, “Polo Silk,” “Mr. Lo Orleans,” “The Picture Man,” and a couple other things. I’m a photographer and cultural bearer from the great city of New Orleans.

What made you pick up a camera?

It’s crazy. My mother’s been telling me lately, “You’ve been groomed for greatness.” I’ve been trying to get used to that idea because I think there’s a point to what she’s been telling me.

My grandmother, mother, and aunts had all these pictures of everybody—family photographs—on the wall. I used to sit in my Aunt Clara’s living room, amazed at all of the photographs. I come from a family that does a lot of reading. We had TIME Magazine, JET Magazine, Sports Illustrated. The stories were good, but the pictures always drew me in. I was always waiting for the next issue to come out.

My photographic journey began at the Boys Club—it’s now the Boys & Girls Club. They had a photography class taught by a guy named Mr. Jim. I’ve been taking photos since then, but I started getting serious about it in ‘86.

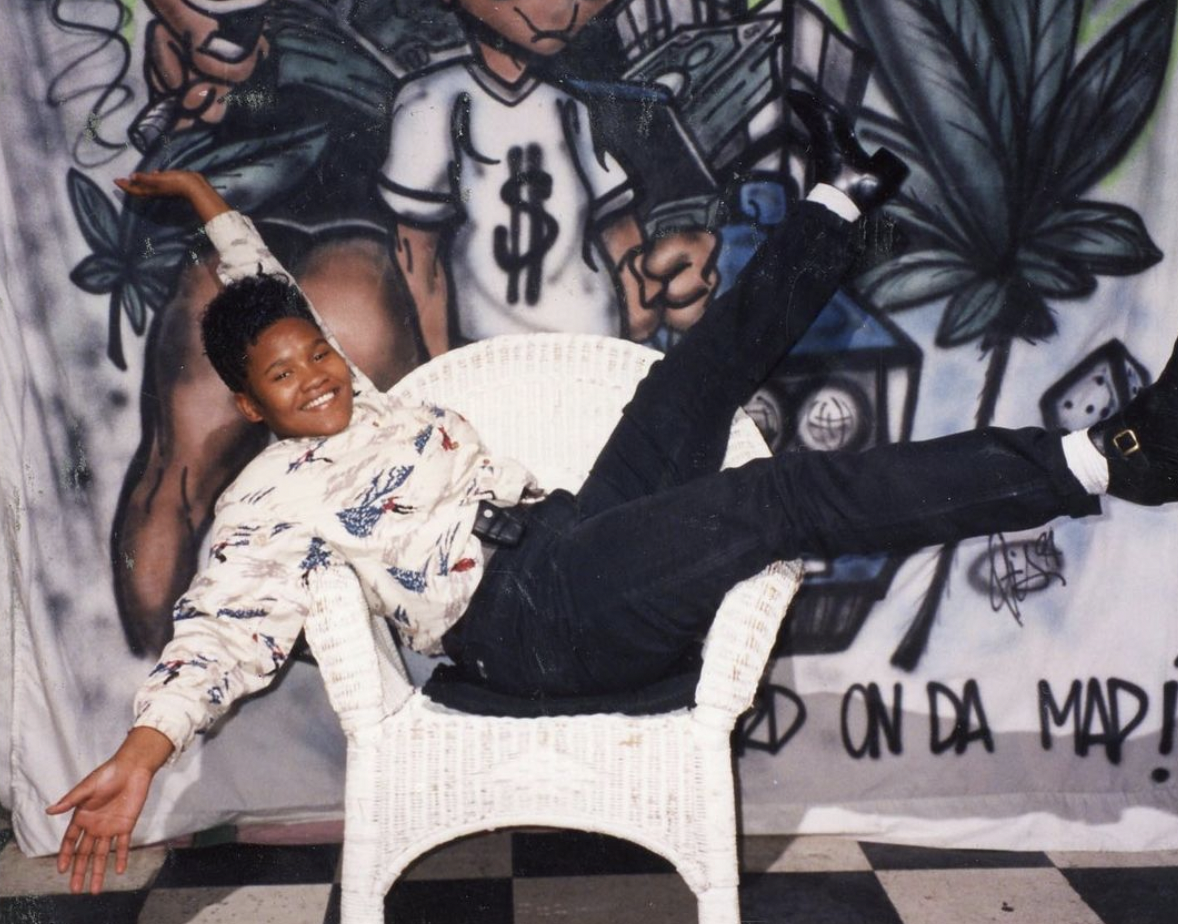

We had a teen club called Club Adidas on Canal Street. This was around the days when hip-hop first started. A rapper named Warren Mayes—he had this song called “Get It Girl,” one of the first New Orleans songs to go national—had a club with a little setup for pictures. As we’re leaving [his club], I’m thinking, “Hold up! I take pictures. We need to make this happen, too.”

By Easter, I had hooked up some stuff. We had an extra room set up like a bedroom, so I tried to make it an extension of my room. I put Polo [Ralph Lauren] shoeboxes on the shelves. I think the first Jordan 3s had come out, so I put them on the shelves, too. Hip-hop had just started, and we had things like Word Up Magazine and Right On Magazine. I decorated the wall with all the hip-hop pictures I could find—LL Cool J, Rakim, everyone. Then, I got the wicker chair, and bam, it was on.

All images courtesy of Polo Silk.

Was Chelsey your first camera?

Yes, Chelsey is my first camera. She’s still in here somewhere. I named her after Chelsea Clinton—it was around when the Clintons got into office.

What kind of camera is she?

My Polaroid camera.

You’ve been documenting Black life in New Orleans since the ‘80s—some might say that makes you a historian. Do you agree?

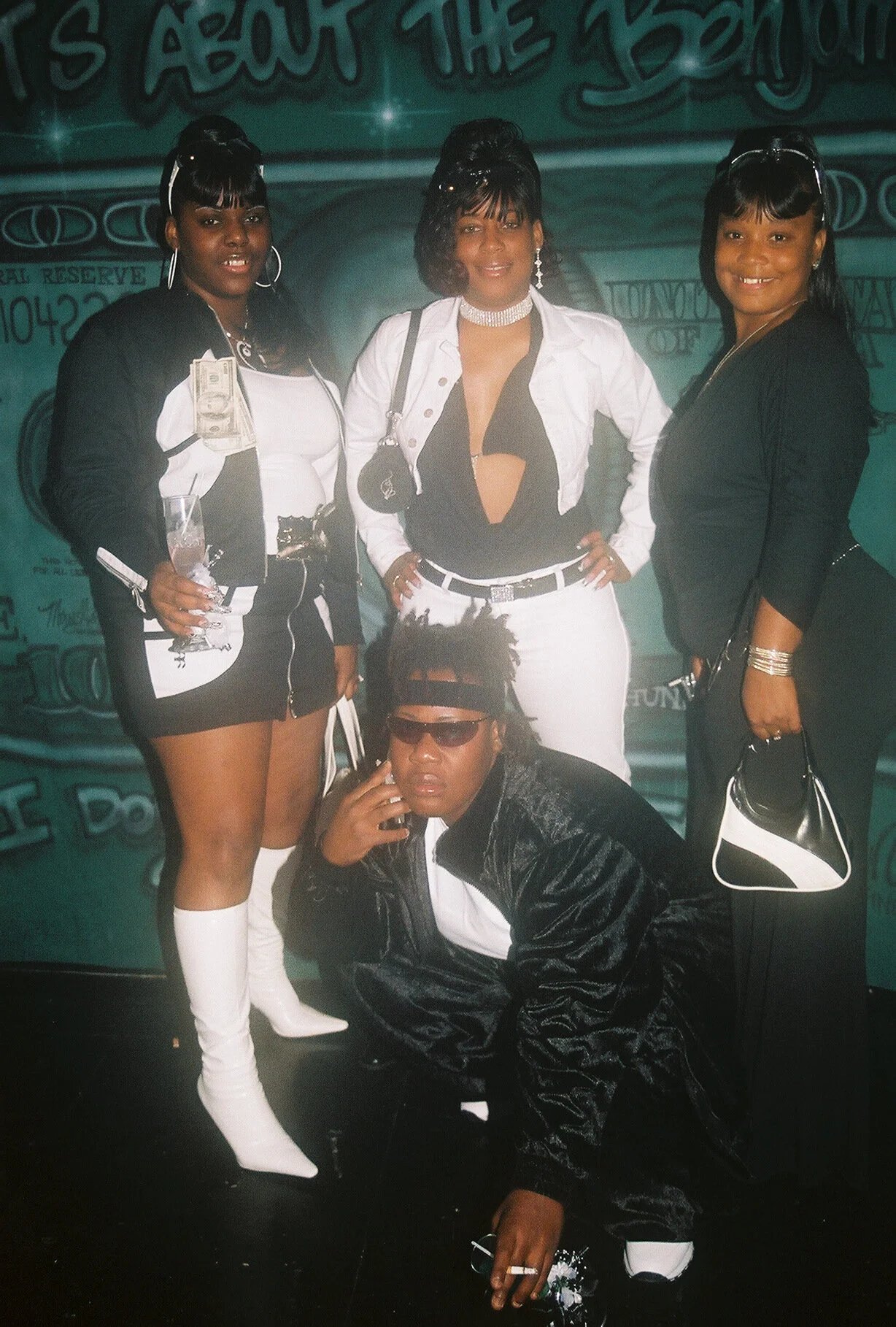

I never looked for this, but that’s how it turned out. I photograph the hip-hop scene, I photograph Second Line culture, and I photograph Mardis Gras culture. A lot of people in my family are in the Second Line culture—my dad used to parade with [Young Men Olympians], and my Uncle Yam had his own Indian tribe. I’ve been around that all my life.

With all the knowledge that I gained from being out there, I’m now one of the leading authorities on hip-hop culture, Mardis Gras culture, Indian culture, and Second Line culture. On the weekends, my phone starts ringing. People know one thing: I’m where the happening’s at. If they don’t know what’s happening on the weekends, they know they can call me. I’m at Second Line, a block party, a night party—I’m at somebody’s party.

“With all the knowledge that I gained from being out there, I’m now one of the leading authorities on hip-hop culture, Mardis Gras culture, Indian culture, and Second Line culture. ”

Are there any major differences between capturing New Orleans culture back then and capturing New Orleans culture now?

There’s a major difference. In the ‘80s, [our parents] worked a long and hard week, but come the weekend, they dressed up to go out. We followed suit and tried to get on our best outfits to go out. Right before the tennis shoes took over, we’d put on our best dress shoes with our outfits. We used to be dressed to the nines. These cats now just throw on a new pair of Jordans or whatever new kicks are out—Yeezys or whatever’s out—and a white t-shirt.

In our era, if you had on a pair of $300 Ballys, then you had to have a fresh Polo or a $300 Gucci shirt to go with that. That’s mostly what the change is. We used to put on Polos and things like that, but we had slacks on with them. In this era, it’s the tight jeans or cut up jeans, a fresh pair of kicks, and a t-shirt, and they’re good to go.

I’ve noticed that. I’ve seen that people used to wear suits and get dressed up for the night.

In my era, you’d want to wear a fresh blazer and mess everybody’s head up—everybody was always trying to outdo everybody. If you see a nice Polo blazer, you’re going to get it and try to mix it up on everybody. A friend of mine had a club called New Edition, and he wouldn’t let tennis shoes in there. If I was shooting at another club and knew I was going to New Edition afterwards, I knew I had to bring some [dress] shoes with me because he wouldn’t let you in there with no tennis shoes on. Now, I don’t know the last time I’ve seen kids in a blazer or a tie.

Even out here in New York, some clubs have that policy still—you can’t wear certain things to the club.

I gotta make sure that when I make my way back up there this time, I bring some kicks with me or be ready to go shopping. Ain’t no getting turned around.

You have a large collection of rare images of hip-hop legends.

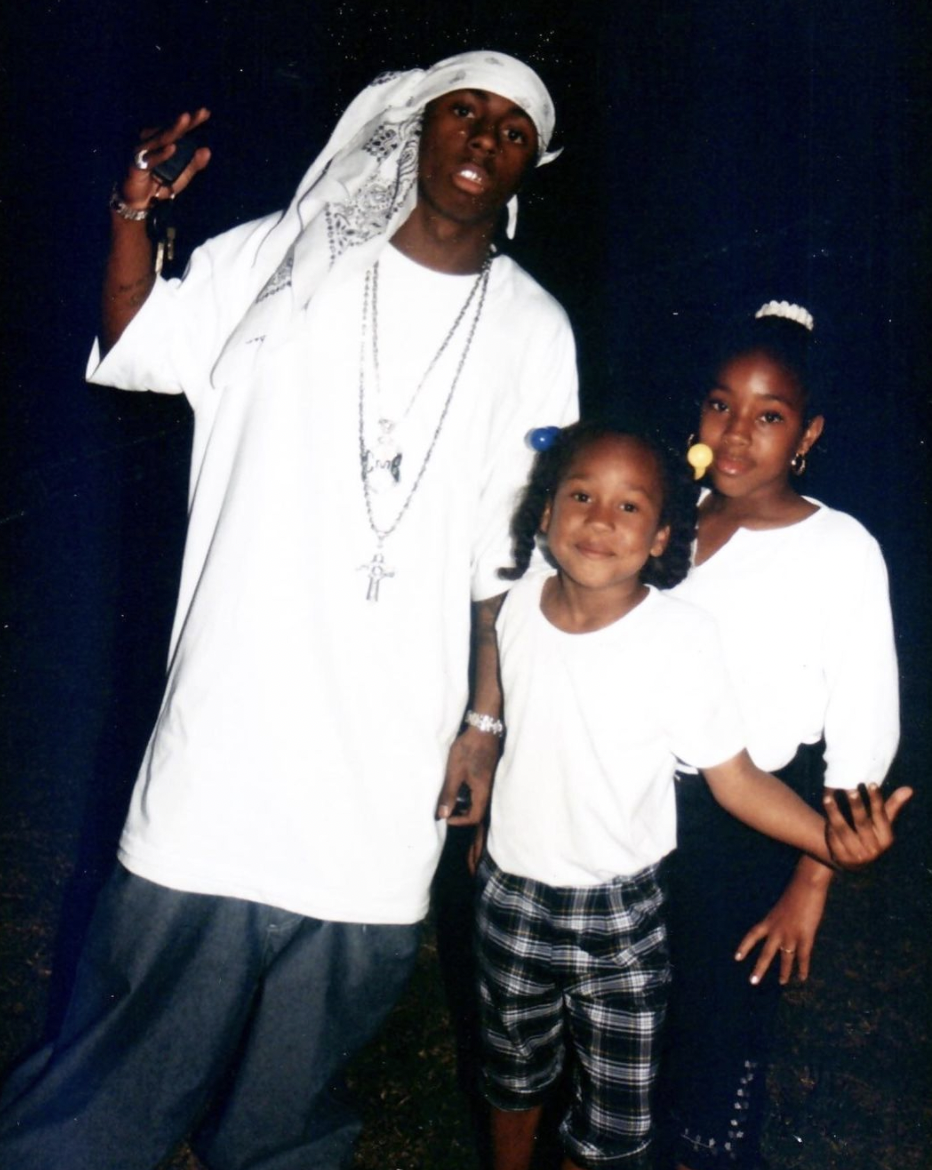

My journey started when LL Cool J started. I even dabbled in rap, but after running into Tim Smooth, Bustdown, Soulja Slim, Juvenile? Man. I was mostly friends with these guys, so it was easy to take pictures of them. It was easy to get a good shot of them without doing the groupie thing.

During that time, we didn’t know that hip-hop was going to make it to the next level. Everyone said that it was a fad and that it was going to be in and out. At my cousin’s club, Big Man’s Lounge, he wouldn’t play rap music until 12AM. You had your early crowd—my mom and dad and all the old people—and then around 11PM, you got a line of people waiting for DJ Jimi to start playing rap music. Once that 12AM hit, the whole night changed. It’s “Where They At?” and p-popping and twerking until the sun came up. Sometimes, people would just come and hang out on their cars, getting their stunt and shine on.

It seems like all of our cultures are similar in a way.

We kind of picked up some fashion trends from New York MCs and put our own twist on it—like Doug E Fresh with the Polos and stuff. That started the craze down here. We tried to emulate that and put our own spin on everything.

“I was giving them something different, instead of that same-old, same-old that had been going on.”

What stands out to me most are the airbrushed backdrops in your photo booths. What’s their significance to you? Who makes them?

My cousin, Otis Spears, makes them. I was trying to get him to come on the Zoom with us, but he doesn’t have his Zoom stuff set up.

[Around 1990], when I first started trying to shift from doing the nightclub stuff, one night, we went to one of the popular clubs in New Orleans. There was this photographer, Button Man—he had the big nightclubs on lock in the city. What I noticed was that his backdrops had champagne glasses, cards, and watches.

I said, “I could do what Button Man is doing, but I want to do something different.” I was part of the hip-hop era—N.W.A. had just started, everybody was wearing the eight-ball jacket, everybody was wearing the Polo shirts. The first backdrop I got was a Raiders backdrop because N.W.A. was just killing stuff down here. I got my cousin to do a Raiders backdrop, an eight-ball backdrop, a Polo backdrop, and, of course, a champagne backdrop for everyone who was still dressed up.

I made my backdrops with garment holes in them so that when people took pictures by them, I could flip the backdrops and give them variety. I would start off with the champagne backdrop because people were already dressed up, but if I saw they had on an eight-ball jacket or a Polo outfit or Raiders stuff, I would flip it because I had a backdrop that matched their outfits. That brought that attention to me. Once the word got out about me and my backdrops, people would come wherever I was hanging at that night to take a picture by me. I was giving them something different, instead of that same-old, same-old that had been going on.

That’s how you knew you had something.

Nobody had thought of that. People would come out with maybe one or two backdrops, but I was coming out with four. Every time something new would come out—like “Money and the Power” with Scarface or “Get Your Shine On,” “Bling Bling,” Cash Money—I had to have that. Like Rakim said, “I can take a phrase that’s barely heard, flip it—now it’s a daily word.” When songs became like that, and everybody around the city was playing it, that’s the new backdrop right there.

Tennis shoes come out every Tuesday now, but back then, the Jordans came out once a year. I would hit Foot Locker to see what the hottest tennis shoes were and what color scheme was in there, so I could incorporate the color scheme into my backdrop. In New Orleans, we start with our tennis shoes, and then we find an outfit to go with them, so that drew people to [the backdrop]—it matched what everybody was wearing.

Which backdrop was your favorite out of all of them?

I had one that my cousin did for me with Barack Obama, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. on there. Then on the bottom, I laced it up with all the famous people in Black history, but I also put my personal heroes like my mom, my aunt, and my dad. It was an honor to put the ladies that raised me and some of the men that raised me on there, too, because they were history makers for me.

I used to tell kids, “If you could pick out any one of them names on there and you can tell me something about these Black history makers, I’ll give you the picture for free.”

In 2017, you released a book called POP THAT THANG!!!, a photobook featuring hundreds of images of Black New Orleans over the past 30 years. What’s the story behind that?

POP THAT THANG!!! comes from my friend Bust Down. When he was with Luke Records, he made a song called “Pop That Thang” that went national—it’s like p-popping and twerking. When it first started, we called it “pussy popping.” We had the Ghost Town Pussy Poppers at this one club where [MC TT Tucker] and [DJ Irv] used to be at on Fridays—Newton’s. This place used to be bananas on Fridays. Big Man’s and Newton’s were the two spots where twerking and hip-hop started. DJ Jimi was at Big Man’s and Newton’s. Irv and Tucker were at Ghost Town.

Tell me about your collaboration with the Smithsonian.

One of my teachers, Eric Waters, had done a project with them. He had gotten wind that the Smithsonian was trying to put out their first ever 12x12 coffee table book on hip-hop. He told them about my work.

When I got a call back from [the Smithsonian about the collaboration], I was in the hospital. I got into a car accident six years ago—I stayed in the hospital for, like, four months and got six surgeries on my leg. They were saying that they were getting ready for the deadline. I thought I was going to miss out on it, but Eric told them about my situation, and they held the project up for me. I’m thankful and blessed because I sure didn’t want to miss that. When hip-hop first started, I looked up to LL Cool J, Run DMC, Juvenile, Soulja Slim, and other hip-hop artists here. It feels like I’ve been in the green room with all these artists, and now it’s my time to get on stage and perform. I’m blessed that four of my shots are going to be in this book that’s coming out in August.

“It feels like I’ve been in the green room with all these artists, and now it’s my time to get on stage and perform.”

Not only do you go by the name Polo, but you’re also known for wearing Polo Ralph Lauren from head to toe—

Daily!

Why is that brand so important to you?

The older cats who used to dress up would be starched up and dressed up in fresh ‘Los. A good friend of mine, Sporty T—rest in peace—and Gregory D were with the Ninja Crew. In one of their first songs, he said, “Sporty as can be and that’s a fact. With every shirt I wear, my Polo socks will match.” Once that came out and I heard that? We were cool because I was rapping—me and my brother and my cousin were rapping. We were trying to keep up.

My rap name was Polo Silk. “Polo Silk, the ladies’ choice, the man with the looks, and the golden voice. The chocolate treat that’ll knock you off your feet. Come see me, and find the beat.”

At first I was just Silk, but then I became Polo Silk. If I was going to be Polo Silk, I had to be Polo down! Everybody’s always looking for weakness in your armor when you’re battle rapping, so I could never get caught slipping. It just caught on. Most people like to switch up to stay trendy, but I stuck to Ralph because I love it.

Maybe about six or seven years ago, I started finding out about the ‘Lo Head tradition in New York and linked up with a bunch of those cats. We talk a lot on Instagram and Clubhouse. It’s going to be a ‘Lo barbeque in Atlanta for Memorial Day Weekend. I’m looking forward to that.

“If I was going to be Polo Silk, I had to be Polo down!”

What story do you want your photos to tell the world about New Orleans?

They call New Orleans “the city that care forgot.” For a lot of years, we’ve been known as the murder capital. I want my photos to show that it’s not all that bad. I want my photos to show the love and passion we have for each other.

New Orleans isn’t a real big city, compared to New York and Atlanta and Los Angeles—sometimes it only takes 15 to 20 minutes to get from one spot to another—but it’s the love and passion that makes people want to come down here. In other places, they’ll just walk by you, but down here, people just naturally speak to each other. That’s what draws people in. When they come here, they don’t want to leave.

They always talk about our football team, the Saints. They always talk about Bourbon Street and the French Quarters. I want to show the part of New Orleans that people don’t talk about and shine the light on us. Most of my friends and photographers who mentored me—Girard Mouton III and Eric Waters—lost everything in their archives. I’m blessed to still have mine. I have a job and a duty to carry this weight for them and show our New Orleans.

I’m happy that you kept going.

My mom worked two and three jobs to put food on the table. I knew she was tired, but she kept going. That’s where I get that spirit from. That’s why I always tell people that I give thanks to my mom. Six kids on her own. Two and three jobs. My mom comes from Mississippi. It comes from what my people went through in them fields and plantations. You just had to make it happen.

On the weekends, I wouldn’t get no sleep. Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, I’m gone. Sometimes—especially on Sundays—I used to be in the club until 5 or 6 in the morning. I’d have to be at church for 10AM. Second Line starts at 12PM. I hate to say it, but sometimes I’d be looking at the clock like, “Second Line’s about to start. Pastor, hurry up or I’m gonna have to act like I’m going to the bathroom and ease out the back door.”

But my job wasn’t hard. I got to enjoy myself, have fun, and make money. Yeah, you go through your ups and downs, but it was more blessings than anything. I got a chance to show New Orleans through all the people who gave me the honor of photographing them.

I know for a fact that you still have some unreleased photos.

Oh yeah. I be telling people, “I don’t even think that’s 20 percent, what I have up on Instagram.”

“I have a job and a duty to carry this weight for them and show our New Orleans.”

Thank you so much for this. I’ll be seeing you soon. I’m gonna come out there very soon.

And imma be trying to come out there to your end soon. The love I’ve been getting from New York has been unbelievable—from Atlanta, Dallas, Los Angeles. I’ve been working on getting a pop-up in all these cities.

If you come out here, you and Jamel Shabazz—

That’s the first place I’m going when I get to New York! To his house!

Any last things you want to say to the people?

I’m Polo Silk. Lo Orleans is my New Orleans. I say Lo Orleans because most of the problems we have in this city are because everybody is representing their projects and their wards. I’m from Uptown, so other people say, “You’re always putting up them people from Uptown! We took pictures with you, too!” And I’m thankful for all the people in New Orleans—the whole greater New Orleans area—so I keep it at Lo Orleans.

When Uptown was beefing with downtown or when Calliope was beefing with Magnolia, or 3NG was beefing with other people, Chelsey had enabled me to go to spots where I wouldn’t have been able to go. My camera and the way that I carried myself. The way you present yourself and carry yourself will open more doors for you than anything in the world.

I’m thankful for all the people in Lo Orleans who gave me the opportunity to follow them. Every opportunity and every door that’s opening up is not just opening up for me—it’s opening up for all of us. I’ve been going around and telling people, “If I never told you before, thank you.” God is opening up some amazing doors for me, and I’ll never forget the people who were there for me. POP THAT THANG!!! sold in 18 countries. A shoe deal with Reebok. That stuff don’t happen where I come from, but it’s been a blessing.

“Every opportunity and every door that’s opening up is not just opening up for me—it’s opening up for all of us. ”